Exploring the Rise of Congenital Syphilis in California and Louisiana

Congenital syphilis (CS) is caused by a bacteria called Treponema pallidum passed from mother to child during fetal development or at birth. CS is entirely preventable through prenatal screening and treatment of an infected pregnant woman. Despite its preventability, there were 918 recorded cases of congenital syphilis in the U.S. in 2017 – a 44 percent increase since 2016 and a 153 percent increase since 2013 (Figure 1)1,2

Figure 1. Troubling rise in syphilis among newborns, Reported STDs in the United States, 2017 1

Researchers from the UC San Diego School of Medicine1 and Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine 2 collaborated to assess two of the most severe CS outbreaks in the U.S., affecting Kern County, California and East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with prenatal care providers and focus group discussions (FGDs) with high-risk pregnant women. The goal of this qualitative study was to (1) understand the contributing factors to these two CS outbreaks and (2) identify missed opportunities for prevention and improved screening and treatment.

The research team interviewed a variety of prenatal care providers, including obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs) and maternal-fetal specialists, who work with high-risk pregnant women. Most providers interviewed had over 5 years of prenatal care experience.

Of the high-risk pregnant women in the FGDs, many were from low socioeconomic backgrounds and members of racial and ethnic minority populations. “High-risk,” defined by providers, encompasses on a variety of factors including: drug or alcohol use while pregnant; having unprotected and/or transactional sex; having coexisting health conditions (e.g. diabetes); being homeless or marginally housed; living in an area with high prevalence of syphilis or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Prenatal Care Providers (Both Sides)

Most of the prenatal care providers had only received formal training to diagnose and treat syphilis during medical residency, which for many, occurred several years ago. Many providers referenced the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for testing and treating pregnant women for syphilis.

Providers faced challenges in communicating with patients, as some pregnant women were distrustful of the information they were given or fearful of testing positive for drug/alcohol use.

There’s so much stigma about medical care… Women have fears, like doctors only want to take my baby away, they’re only going to get me in trouble… they’re not going to help me… If there was just more of a collaboration, instead of an “us against them thing.” If they thought of our clinics as an actually partner instead… – OB/Gyn in East Baton Rouge Parish

Prenatal care providers also expressed concerns regarding testing the partners of syphilis-positive patients. Even when they advised partner testing, the providers had no assurance it took place. Further, some patients feared asking their partners to be tested and/or lacked a way of contacting their previous partners.

High-Risk Pregnant Women (Both Sides)

A major gap in preventing CS was a delayed initiation of prenatal care, as late as the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Some pregnant women did not receive care until birth. These trends were directly linked to barriers women faced, including: limited resources (e.g. transportation); homelessness; drug/alcohol abuse; language barriers; competing health priorities; and being an undocumented immigrant.

Many pregnant women felt judged or as if providers were trying to rush them out, creating mistrust. Trepidations grew particularly for active or recovered substances users, homeless women, undocumented immigrants, and women in violent relationships. Women feared receiving a warrant or that child protection services would take their children away, causing some to evade prenatal care until birth.

Women in both states understood the basics of STI transmission and prevention. However, few participants knew the detailed effects of CS, especially long-term harms for babies (e.g., stillbirth, blindness). As they learned more dangers of CS, interest mounted for advocating increased education and prenatal care. Raising awareness would inspire more screening for syphilis and improved adherence from patients.

High-Risk for Pregnant Women (Kern County, CA)

In Kern County, CA, most pregnant women struggled with transportation. Despite some local insurance plans offering transportation services, most women found it difficult (and sometimes impossible) to access healthcare – both in general and during pregnancy. Few participants had their own cars, while many were unemployed and could not afford transportation fare.

Pregnant women who were homeless or non-native English-speaking reported feeling embarrassed and stigmatized in clinics and insurance offices. These experiences discouraged them from attending appointments or applying for insurance. When they did seek health information and resources, many faced aggression or a lack of compassion from their providers.

A lot of homeless people that try to go in for just the medical coverage… People tend to look at them like thy’re pretty much beneath us… They tend to not want to try and go get help… (A) because they can’t read and (B) because they figured that they’re not going to get anything because they have no place to live. – FGD participant in Kern County

High-Risk Pregnant Women (East Baton Rouge Parish, LA)

In East Baton Rouge Parish, LA, insurance was the greatest barrier to accessing effective care. A confusing application process, approval time, search for providers, and long waitlists all delayed by patients’ first prenatal care visit and overall treatment. At times, women resorted to accessing care outside of East Baton Rouge Parish or at urgent care offices.

LA focus group participants also frequently described limited trust in their intimate partners. Specifically, many women doubted their partners were faithful and/or practiced safe sex. Even if an infected pregnant women was appropriately treated, she could be re-infected by a partner who was untreated and/or had a different syphilis-positive partner.

Despite proper screening for syphilis, few participants were aware of the congenital syphilis outbreak in Louisiana. Some doctors did not provide in-depth information unless specifically asked or if there was a positive result.

They just tested me for it [syphilis]… I have had EDUCATION on syphilis and stuff in the past. But not… what it can do to the baby… As far as pregnancy, no doctors have discussed… pretty much ANY STD with me. – FGD participant in East Baton Rouge Parish

Syphilis Care Continuum and Recommendations

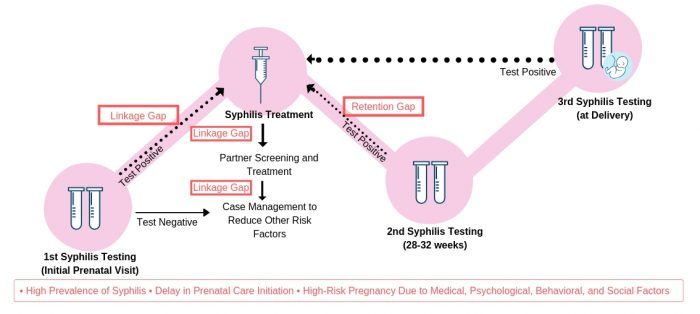

Based on our findings, we created a congenital syphilis care continuum framework (Figure 2) to outline the sequential steps of syphilis testing, care, and treatment that syphilis-infected pregnant women go through from initial diagnosis to treatment to being cured. The care continuum framework highlights where linkage and retention gaps occur at each stage.

Figure 2. Gaps in testing and treating syphilis among pregnant women in East Baton Rouge Parish, LA and Kern County, CA.

Recommendations emerged, during interviews and focus groups, on how linkage and retention gaps could be reduced during syphilis screening and treatment:

- Explain the value of prenatal screenings and emphasize long-term risks for baby;

- Promote public service announcements on the rise of congenital syphilis on social media platforms;

- Encourage feasible ways for pregnant women with syphilis to notify their partners to get tested;

- Reduce institutional barriers pregnant women face when seeking prenatal care;

- Implement rapid point-of-care screenings in the field.

Authored by: Julie Yip, Eunhee Park & Jennifer Wagman

References:

- HHS, CDC & NCHHSTP. CDC FACT SHEET Reported STDs in the United States, 2017.

- Bowen, V., Su, J. Torrone, E., Kidd, S. & Weinstock, H. Increase the Incidence of Congenital Syphilis – United States, 2012-2014. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 64, 1241-1245 (2015).